An interview with Suman Khatiwada, Scientist Founder of Syzygy Plasmonics

Revolutionizing Chemical Production with Light-Driven Technology

Welcome to the Scientist Founders Interview series, “where scientists showcase their journey toward founding groundbreaking tech startups.

Want to discover invaluable advice for future scientist founders?

Suman, founder of the Syzygy Plasmonics: “The key difference between entrepreneurs and others with great ideas is the courage to act. Expect to work harder than ever; being an entrepreneur is the best job in the world if you value growth.”

Key point:

Find the Right Co-Founder: Suman Khatiwada’s partnership with Trevor was crucial. A co-founder who complements your skills and shares your vision can significantly enhance your startup’s success.

Courage to Act: having an idea is only the beginning; the willingness to act on it makes a difference.

Framework for Success: Utilizing a structured framework like TMI (Technology, Market, Impact) ensures your idea is innovative, marketable, and impactful, guiding your venture toward success.

Leveraging Networking: Aspiring scientist-founders should actively seek out networking events, mentorship opportunities, and collaborative projects to gain insights, support, and resources that can propel their ventures forward.

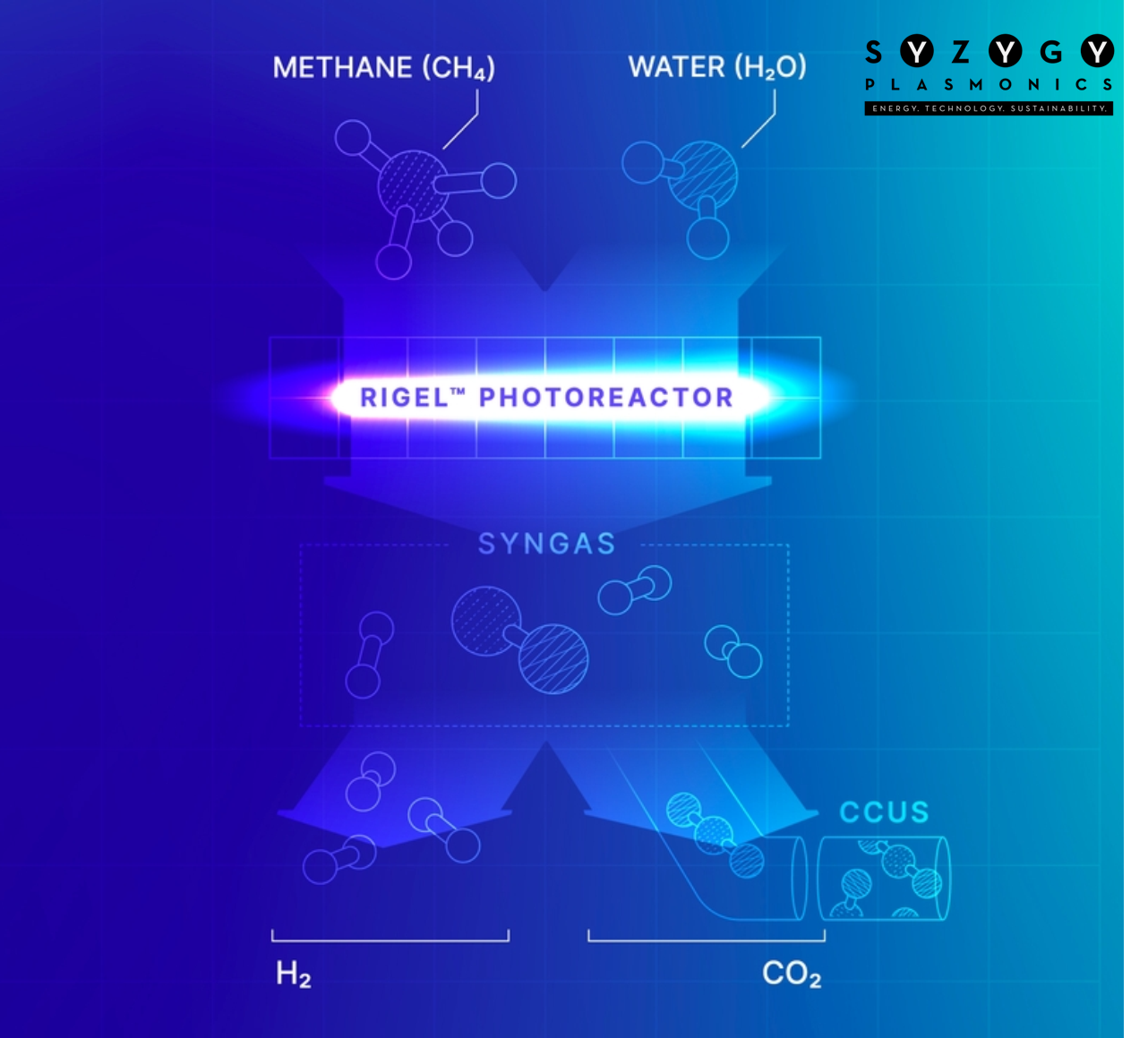

In the evolving landscape of energy transition challenges, the need to decarbonize hydrogen and ammonia production is paramount. Leading this innovation is Suman Khatiwada, founder of Syzygy Plasmonics. Syzygy Plasmonics is revolutionizing the industry with its all-electrical chemical reactor, which uses light-driven chemistry to produce high-value molecules more sustainably and cost-efficiently than traditional methods. The company's mission is to create a world where chemicals, fuels, and fertilizers are low-cost, carbon-neutral, and accessible to everyone.

Read Suman’s interview about how he transitioned to become a Scientist Founder

Can you share the history of your journey in the labs?

My journey began during my undergraduate years at Morgan State University. I majored in physics and got a taste of research by working in a lab focused on magnetic and carbon nanomaterials.

In the last two years of my schooling there, I joined a lab to do research in nanotechnology, the latest exciting science field, around 2006. I worked on magnetic materials and carbon nanomaterials, published papers, and presented conference posters. We were doing something meaningful, sharing it with the world, and receiving recognition. It made me feel good., I was like, "Oh, this is great. Like we're doing something and telling the world about it, and people actually care." They are paying attention and I get to see places and meet new people.

This spurred my decision to go to graduate school for a PhD because I craved more deep science exploration. I chose Rice University in Houston, TX, where I started my PhD program in 2008. At Rice, collaborating with NASA, I worked on carbon nanomaterials in composite materials for space applications. My work was experimental, as I've always been more experimental. I published a few papers, worked on fascinating projects, ultimately wrote my dissertation, and graduated.

Founder Spark: What key moments or insights during your research ignited the entrepreneurial spark?

A few things happened while doing a PhD at Rice that completely changed my path.

Rice University has the Rice Alliance, which hosts the Rice Business Plan Competition (RBPC), business plan competition. Attending this competition since 2010 opened my eyes to a different world. Rice's PhD or MBA, with their ideas either from their laboratory or just a business model innovation, start these companies, telling the world, winning hundreds of thousands of dollars in prize or equity money, and trying to go and start a company. I was like, "Oh, this is amazing." I talked to them and said, "Oh, they're not that different from me."

Then, a Technology Entrepreneurship class taught by Tom Kraft, a vital mentor early on, was particularly impactful. Teams of MBA and PhD students would create companies based on Rice University patents and submit business plans and pitches. This hands-on experience was invaluable.

Additionally, participating in the Rice Center for Engineering Leadership's (RCEL) annual Ignite trek to Boston and visiting companies like Greentown Labs and A123 Systems made me realize I might enjoy entrepreneurship more than academia. I discovered my strengths in understanding deep science and articulating it to others, which suited me well for a career in deep technology entrepreneurship.

How do you pursue this fire of creating something impactful?

So with that mindset, I was like, This is the last year of my PhD "Alright, I'm going to try to find something." What I found was an internal project. In the last year of my PhD, I joined forces with friends to work on a lithium-ion battery-based spray-paintable battery technology. We founded Big Delta Systems, which today enPower. However, my visa situation prevented me from immediately pursuing this entrepreneurial path, so to strike on my own with a considerable risk of not getting my path to my green card, I would be in limbo. So, I spoke to a few immigration lawyers. All of them said, "Don't be stupid. Get a job. Let these patents and a couple of your papers publish, and then maybe you'll have enough of a profile to get a green card, and then you can do it. Otherwise, you put yourself at risk of having to leave this country." Once the third immigration lawyer said the same thing, I said, "OK, alright." ....so I took a job at Baker Hughes.

How did you change from academia to starting a company and then working at a more prominent company like Baker Hughes?

My journey at Baker Hughes started as a bench scientist, rapidly advancing to technical lead. I spearheaded projects from ideas to prototypes, securing six patent families.

Transitioning from academia to a corporate role was challenging. The corporate environment required a different approach: navigating administrative hurdles, understanding market needs, and aligning scientific objectives with business strategies. I had to convince stakeholders of my ideas… One of my notable patents involved a solid propellant used to open a valve. Similar research was applied to the solid propellants used in airbags and rocket technology, which rapidly convert from solid to gas. Through applying this knowledge, I developed a solution for oil and gas applications. I proposed, "Wouldn’t it be nice if this solid propellant could be run from electricity and not have any organic solvents?". I created and tested the prototype, presented its value proposition, navigated the stage gate process, and convinced stakeholders, including vice presidents. This kind of experience taught me the intricacies of product development and corporate dynamics, shaping my ability to bridge the gap between science and business and laying the groundwork for my entrepreneurial ambitions.

It was a valuable learning period, but I knew that I wanted to create something.

What motivated you to start a company again?

I always knew I wanted to start a company. After a year and a half at Baker Hughes, my profile was strong enough to apply for a green card. Around this time, I met Trevor, today's Syzygy CEO, a senior manager at Baker Hughes. We started every Thursday afternoon gathering called "energy lunch" to discuss new ideas in energy transition with a group of 8 to 16 people and maybe to be adopted inside Baker Hughes.

There was one particular idea that we presented to the C-Suite, but it was around the same time that the oil and gas industry was in a downturn. The company was going through layoffs, and we were told this was not the right time—just focus on your job. That was the spark for us to think, "We are not going to be able to do what we want with our lives," which set our determination to pursue our entrepreneurial dreams.

How did you identify ideas for becoming a founder?

We worked independently every evening of the week and together every Saturday. We created a framework called TMI: Technology, Market, Impact to scout potential ideas. We wanted to work on deep technology where we could control the IP, ensure it was new and exciting, and bring something new to the world. M was for market potential, and I was for impact, a positive impact on people and the planet.

First, we tried to start a water filtration company. We created a device with a sponge coated with some nano-silicon coating inside for disaster situations. We quickly realized the IP could have been better; many companies were fighting against each other, so we dropped that.

....and then Syzygy?

In 2016, a Rice University paper on a photocatalyst caught our attention. The paper showed a process dealing with ethylene, an economically important molecule. Assuming the photocatalyst could handle other hydrocarbons and reactions, we considered building factories and running them with solar or artificial light. The market potential was global, and the impact was huge, reducing carbon emissions. TMI was a perfect fit. I contacted the inventors, Professor Naomi Halas and Professor Peter Nordlander.

We met with the professors weekly for the next nine months, used them as accountability partners, and sent them reports. Trevor and I worked every Saturday all day and on our own every evening. After seven months, it looked probable that we could have a business out of this. That's when we decided to quit our jobs at Baker Hughes and start the company together.

What are Syzygy's achievements in terms of milestones, fundraising, and collaboration with Rice University?

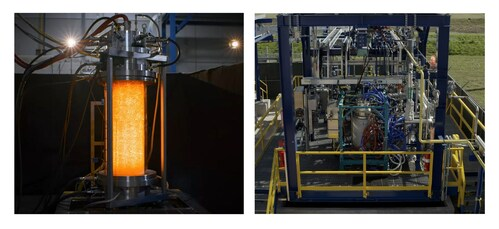

Go-to-Market Reactor: Our go-to-market reactor, Rigel is being tested at our industrial scale Demo Plant in Pearland, Texas – just outside of Houston, produces 230 kilograms of hydrogen daily from ammonia as a feedstock. This fully electrified unit replaces combustion with electricity, eliminating point source emissions.. Recently, we created our first jet fuel from our CO2-to-fuel pathway in a successful field trial in North Carolina.

Fundraising Journey: Raising Series A was a significant challenge. We faced a setback when an investment fell through, which was a dark moment for Trevor and me. We had to pick each other up and strategize to keep going. Forming a cohort of angel investors, we secured the first million dollars, which helped attract venture capitalists. We raised $9.7 million in our Series A round, followed by $24 million in Series B, and $76 million in Series C in November 2022. Each round brought different challenges, with increasing investor expectations regarding our company's readiness, customer traction, and market potential. Our intellectual property (IP) strategy has been crucial, ensuring we have the freedom to operate and create value for our investors.

Growth and Collaborations: We’ve raised about $115 million, expanded to 120 employees, and are on the verge of market entry. Our commitment to innovation is reflected in the dozens of patents we’ve filed, many in collaboration with Rice University. One of our key team members, Dr. Hossein Robatjazi, was a graduate student in Professor Halas's lab and is now our VP of research. r. We hire interns from Rice and conduct characterization work there, maintaining a strong, mutually beneficial relationship with the university. Additionally, I mentor at the Rice Energy Clean Accelerator, teaching classes and advising technical founders as a way to give back to the community that has supported us.

What advice would you give to scientists considering the transition to entrepreneurship? What would you have liked to know when you started?

I’ve found a few things about people, especially those who’ve been in academia and gone through a PhD. one key insight I've gained is that societal pressures, especially around the age of 30, can steer many towards stable jobs instead of following their passion. The critical difference between most people and successful entrepreneurs is not just the idea but the courage to act on it. Many smart individuals have great ideas, but few execute them. Ensure you have a supportive network, whether it's your spouse, family, or friends, as their backing is crucial.

Understand that this journey will be challenging, requiring sacrifices and resilience. Expect to work harder than ever, much like raising a child, requiring immense sacrifices. The relationship with your co-founder is as significant as any close personal relationship; understanding and harmony are vital. The initial phase will be tough, with little financial reward, but the intellectual stimulation and sense of worth from working on something impactful are incredible. This journey will make you a more well-rounded individual, teaching you to be a good businessperson, scientist, and leader.

It’s the best job in the world if you value growth, intellectual stimulation, and making a positive impact. Financial success isn’t guaranteed, but the journey itself is immensely rewarding.